Peter Werbe is particularly bemused that he and Harvey Ovshinsky are Zooming with me. For more than 50 years, Werbe has edited the underground, radical magazine The Fifth Estate that Ovshinsky founded when he was just 17, so the idea that ĖĮÐÄvlog°ēŨŋ°æ Detroit, an uber-mainstream magazine known best for coverage of celebrities, fashion, and food, finds their work of interest entertains him. âThat must mean weâre not a threat any longer,â Werbe, 81, says with a chuckle, thinking about the years he lived under FBI surveillance. âBack in the 1960s, just because of the way we looked, we probably couldnât have gotten through the door.â

Perhaps, but anything that lasts 55 years and counting deserves respect. And the fact that both Detroit natives have published their first books at roughly the same time this spring â Ovshinskyâs is a memoir, and Werbeâs is a semi-autobiographical novel full of violence and sex set during the 1967 Detroit Rebellion â is as good a reason as any to reflect on what the publication they have in common has meant.

This report is hardly the first mainstream moment for The Fifth Estate. Five years ago, for its 50th anniversary, the Detroit Historical Museum and the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit both mounted extensive, celebratory exhibits about the publicationâs history. âI suppose when youâre around for 50 years, you do get to be a part of the cityâs fabric,â Werbe says.

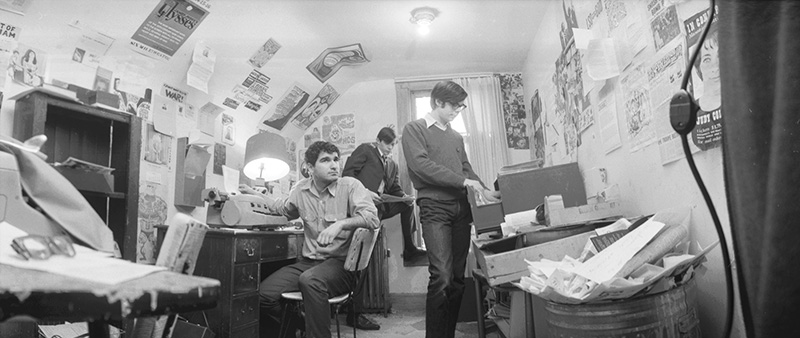

For the uninitiated, Ovshinsky founded The Fifth Estate in 1965 as a DIY project produced on his typewriter and mostly aimed at providing the cityâs nascent hippie generation with news and information about civil rights and anti-war protests as well as a gritty, alternative arts scene ignored by the major daily newspapers. Werbe came along the next year with a more strident, anarchist-empathetic perspective and eventually took over when Ovshinsky, who had become bored of the publishing grind and increasingly at odds with Werbeâs more extreme bent, was drafted into the military. (He served locally as a conscientious objector.)Ėý

The two friends never had a John-and-Paul-style schism, but neither did they ever â until our Zoom â hash out their disparate views on the publicationâs purpose and legacy. Ovshinsky, 72, enjoyed a mainstream media career that included Peabody-winning documentary films and a stint in management at Detroit Public Television. Werbe remained ensconced in anarchistic politics and held forth for decades as a local talk radio host and purveyor of The Fifth Estate, which, since the 1970s, has published quarterly.

Still, their lives are entwined by a scrappy magazine that was a forerunner to alt-weeklies like the Detroit Metro Times. Their book tours â basically a series of online talks thanks to COVID-19 â draw fans who credit The Fifth Estate with their political and social awakenings.

âThe older generation, of which Harvey and I are part, like to look back and be reminded about our ethical choices, recreational choices, and music choices,â Werbe says. âYounger people today in the new movements for social justice like Black Lives Matter look back and they say, âThatâs another era in which people confronted authority.â â

Yet a big irony of what The Fifth Estate became is that Ovshinsky was never a die-hard radical. Whereas many kids moved left in the â60s to rebel against conservative parents, Ovshinskyâs father was a prominent leftist who harangued him to participate in demonstrations. âHe chastised me hard because I wanted to stay home and watch The Twilight Zone and he wanted me to go picket Woolworthâs,â he says. âHe said, âHarvey, do you think Woolworth should discriminate against Negros?â I mean, I was 12 years old!â

Werbe, listening to this, quips: âWell, heâs lucky he didnât turn you into a conservative!â

âWell, Peter, thatâs where you came in,â Ovshinsky answers.

By this, Ovshinsky means that Werbe turbocharged the paperâs leftist conceit. âBetween him and me, we created this newspaper that spoke to and connected to the various communities who were not interested in speaking to each other at the time, even though they were harassed by, arrested by, spied upon by the same police â the druggies, the politicos, the musicians,â Ovshinsky says. Adds Werbe: âAnd also, the Black community and certain whites in the area where we lived. I mean, that was one of the features of the 1967 Rebellion, the integrated looting.â

Werbe says the times pushed the paper farther to the left: âIf weâre serious revolutionaries, the paper had to move with the entire movement at that time.â

Here Ovshinsky pushes back. âYeah, but it didnât have to, Peter. Thatâs where you were at, thatâs where the staff was at. I was no longer there anymore. I never saw the paper as a house organ for the revolution.â

Werbe, astonished by the remark, turns to me: âHarvey correctly tells the story in his book of the anti-war meeting in 1966 when he said, âIs there anyone here who would like to help on the paper?â and I raised my hand. I raised my hand for one purpose: to make it the house organ of the movement.â

Both men erupt in chuckles. âWe never had this conversation! This is great!â Ovshinsky says.Ėý

The Fifth Estate in 2021 has some 4,000 subscribers scattered across the country, and the content is as likely to be about California wildfires or a biodiversity farm in India as it is about Detroit. Most magazines of this ilk died after the heyday of Vietnam and the civil rights movement, but Werbe reinvented theirs in 1975 as a quarterly journal of essays and political analysis on issues broad enough to draw interest beyond Detroit.Ėý

Ovshinsky isĖý proud of the magazineâs survival, even if Werbe did it differently than he would have. âPeter broadened the vision to include the country and the world,â he says. âMy focus as a storyteller has always been Detroit. Thatâs my muse. Thatâs my revolution. Thatâs my preoccupation. Thatâs what I dream about.â

Werbe replies: âListen, thatâs how the magazine survived. If I could have, like we used to have, 100 different places in Detroit selling it and young people lining up outside getting the latest issue to take it out on the streets to sell, Iâd be there in a second. But we had to evolve.âĖý

|

| Ėý |

|