Centennial anniversaries are milestone events, whether for a person, institution, or country. The United States’ centennial in 1876 was a countrywide celebration of freeing ourselves from British rule. Jimmy Carter turned 100 recently, the first U.S. president to live for a century. On June 11 of this year, another former president made news when Barack Obama strode onto the stage at the Detroit Institute of Arts during the “Kresge at 100” celebration, marking ’s centennial year as a philanthropic force in Detroit and beyond. The 44th president was a surprise guest, and the delighted audience gave him the ovation befitting a political rock star.

For the next hour, Obama and the foundation’s president and CEO, Rip Rapson, discussed their shared belief that cities drive America’s economy. They talked about the hellish years of 2008 and 2013, when the bottom fell out of the economy everywhere, but in Detroit especially; the automobile industry skidded into bankruptcy; the mortgage crisis hollowed out the housing market; and corruption scandals tainted city hall — what Rapson called a “convergence of terribles.” Then-President Obama did not give up on Detroit; in 2009, his administration bailed out the auto industry while pumping in more federal money. After 2013, The Kresge Foundation and other philanthropies contributed hundreds of millions of dollars to the cause, part of the so-called Grand Bargain to save Detroit.

As Obama told Rapson, “What you are seeing here in this city is a testament to the capacity of people of goodwill working together and institutions like Kresge taking some risks and making some strategic investments but being willing to plant a flag. And people converge around that, and it creates a sense of hope and momentum.”

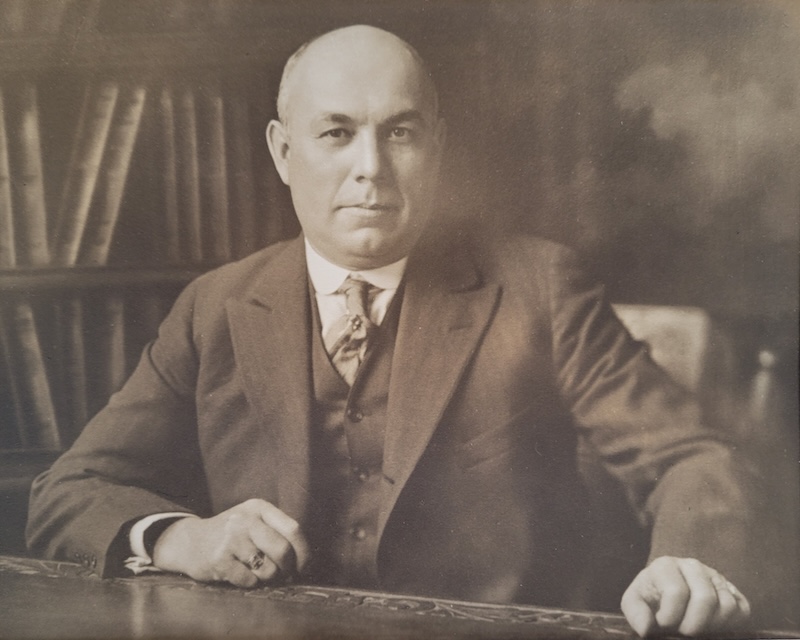

For 100 years and counting, The Kresge Foundation has been a partner in keeping Detroit humming, throwing its considerable capital, both financial and human, behind causes and projects that promote human progress and equity. The foundation has morphed considerably since 1924, when five-and-dime store tycoon Sebastian S. Kresge established his eponymous foundation with $1.3 million in cash and stock “to help human progress through benefactions of whatever name or nature.”

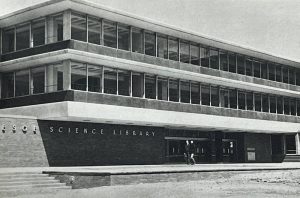

His first donation was $100 to The Salvation Army of Detroit. A 1926 grant helped to fund the construction of the Detroit YMCA and build and support a new home for orphans and neglected children. Kresge’s focus on low-priced household items helped the company weather the Great Depression, during which the foundation resolved the debt of struggling Detroit churches. In 1947, Kresge gave its first grant to UNCF (), an educational nonprofit that raises funds for historically Black colleges and universities. Libraries, dining halls, schools, performance venues, and gymnasiums across North America bear the Kresge name, including at Wayne State University and the University of Michigan. The foundation and the stores were separate entities, though S.S. Kresge contributed stock and real estate to his philanthropy until his death in 1966.

In 1962, as retail trends shifted to the suburban megastores, the company opened its first Kmart in Garden City. The chain of stores grew to 1,200 nationwide, second only to JCPenney in retail sales. In 1977, the S.S. Kresge Co. changed its name to Kmart Corp. and decamped from its Albert Kahn-designed corporate headquarters in downtown Detroit to Troy. In 1987, the company sold the last of its Kresge stores; the last full-scale U.S. Kmart closed this past October.

The Kresge retail empire may be history, but its legacy of good works lives on. Thanks to shrewd investments, the foundation’s endowment has grown to almost $4 billion today. It is the largest foundation in Detroit; the second largest in Michigan, behind the W.K. Kellogg Foundation; and among the top 20 largest private foundations in the nation. Kresge gives out hundreds of grants a year to groups large and small in all 50 states. Its American Cities Program, launched in 2015, includes New Orleans; Memphis, Tennessee; and Fresno, California, but Detroit gets the most love: Of the 600 grants given to all projects in 2023, 108 went to Detroit, to the tune of almost $53 million.

Rapson believes that “philanthropy is at its best when it shape-shifts, when it responds to changing circumstances.” Hired in 2006, he took Kresge in new directions right away and it took some by surprise. The book , published by ĚÇĐÄvlog°˛×ż°ć Media, describes the scene. While speaking at a conference six months after arriving, Rapson surprised everyone with his intention of providing “general operating support for cultural organizations of all sorts,” as well as creating annual grants for individual artists — a first for Detroit.

From his office in the Troy headquarters, where a staff of 120 works to implement the foundation’s vast funding programs, Rapson remembers what drove his decision. He comes from Minneapolis, where he headed the — and served as deputy mayor in the late 1990s, focusing on community revitalization. He wanted to replicate that city’s collaborative “arts ecology.”

In Detroit, he says, “there was a long tradition of support for the arts that came out of the automotive industry; if you were General Motors, for example, you put your money into the arts institute or the symphony. But there was no support for … the individual artist who was just sort of scraping by.” He adds, “This is such an incredible community with the traditions of jazz and Motown and poetry — Black poetry in particular. Couldn’t we figure out something that would begin to memorialize just how important those legacy bodies of artistic accomplishment were?”

The Kresge Arts in Detroit program has become a beloved institution. There are three tiers of funding for local creatives: the ($5,000), ($40,000), and ($100,000 given to a local legend every year). The money comes with no strings attached. Longtime arts administrator Tony Whitfield, a multimedia artist and educator who relocated from New York to Detroit in 2020, received a 2023 Kresge Artist Fellowship for individual artists, “which was a remarkable thing and very affirming.”

Whitfield used the grant to expand his home studio, buy a new computer and printer, retire some debt, and pay a young architect he was collaborating with. Best of all, “I didn’t have to worry about finding other jobs. … The fact that this money came in, and it was unfettered, makes it possible for me to move forward.”

Even more remarkable is the lemonade-from-lemons nature of Detroit’s recovery from financial disaster. Rapson had been on the job only two years when the Great Recession struck in 2008, followed by the bankruptcy crisis of 2013. Kresge jumped in to fill the gap in municipal services, helping to buy police cars and ambulances and to protect pensions from creditors, who wanted to sell off the DIA’s art collection, a city asset. (It’s now held by a trust.) For a foundation to assist in municipal affairs was unusual at the time, but Rapson was just getting started. Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan also spoke at the centennial gala that night in Midtown, saying, “The recovery of Detroit started right here, and Rip Rapson and Kresge had a lot to do with it. … Thanks to our partnership, we’re on our way back.”

They also had a lot to do with the QLine, the first major U.S. transit project led and funded by both private businesses and philanthropic organizations, along with every level of government. Embracing a City describes the 10-year roller-coaster effort to fund and build this 3.3-mile-long streetcar system, with Kresge joining Dan Gilbert, Roger Penske, and many others. At $35 million, Kresge’s initial investment in what was originally called the M-1 Rail streetcar was the second largest ever for the foundation, behind its investment in the Detroit Riverwalk, and other local institutions followed suit. The process had more cliff-hangers than a mystery novel, but Kresge’s energy helped keep the project on track. The system started humming in 2017, and last September, the Regional Transit Authority of Southeast Michigan absorbed the QLine into its operations.

In the Livernois-McNichols community, Kresge’s focus on education reaches full flower. Marygrove College was a failing Catholic college with a magnificent 1920s Gothic Tudor main building. In 2018, it created the , a nonprofit to administer the site. In 2019, the college closed, but Kresge saved the 53-acre campus from foreclosure. Kresge and its public and private partners have transformed the site into a “cradle to career” campus with a cheery new early-learning center, a new public school, and a high school in the historic main building. There is also housing for undergrads from the , a partner in Marygrove’s transformation.

The campus’s mission is to prepare children to be leaders and innovators. Like a stone thrown into a pond, Kresge hopes its success will ripple outward into the community and ultimately the city.

“Our work in Marygrove is just beginning to have real traction in helping stabilize homeownership and attract new folks into the community” without gentrifying the area and displacing longtime residents, Rapson says. “Our challenge is then to connect the dots, to make sure that these aren’t just isolated pockets but increasingly there are, sort of, sinews that hold the city together. … This is a very different city from where it was 10 years ago. In the next 10 years, it’s that connective tissue that will determine whether Detroit really can emerge with a new vitality and energy and health.”

Or, as Obama summed it up that starry night last spring, “I could not [be] prouder of the progress that was made. But there’s still more progress to be done.”

This story originally appeared in the December 2024 issue of ĚÇĐÄvlog°˛×ż°ć. To read more, pick up a copy of ĚÇĐÄvlog°˛×ż°ć Detroit at a local retail outlet. Our will be available on Dec. 9.

|

| Ěý |

|