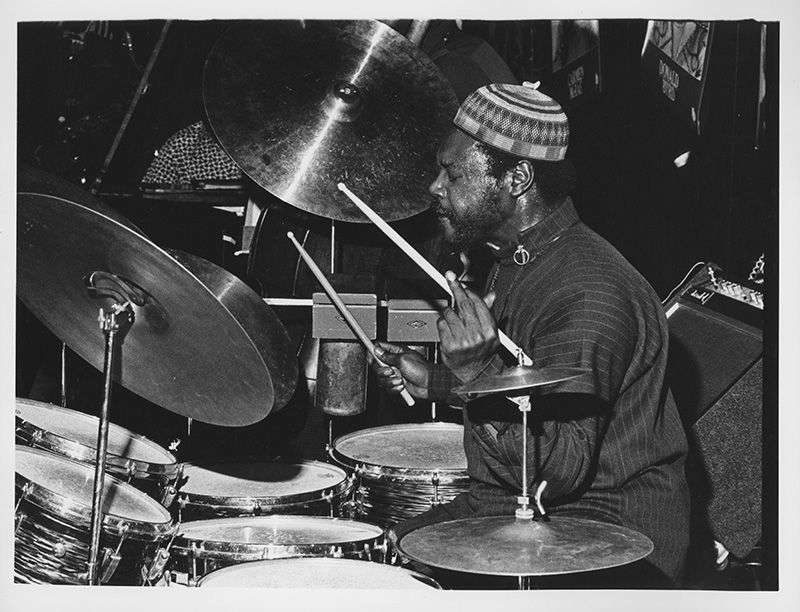

Roy Brooks was a monster with a pair of drumsticks in his hands. Born in Detroit in 1938, the percussionist played with the intensity of Elvin Jones and the strength of Max Roach.

But Roy Brooks was a different sort of monster the day he held a machete in one hand and a bullwhip in another as he threatened yet another neighbor in the old West Side neighborhood where he grew up.

Unlike the floating triplets and off-beat accents that he played with precision and control, Brooks could not control the demon that first started roaring inside him in the early 1960s, when he played in pianist Horace Silver’s bands and recorded for Blue Note Records. Diagnosed with bipolar disorder, Brooks would go on and off medications for the rest of his life.

After joining Silver’s band in 1959, Brooks was a mainstay on the New York City jazz scene through the early 1970s, featuring in the bands of saxophonist-flutist and fellow Detroit native Yusef Lateef (1966-1969) and bassist Charles Mingus (1971-1973) and Roach’s percussion ensemble M’Boom (1970-1992), as well as on records with trumpeter Chet Baker and saxophonists Dexter Gordon and Sonny Stitt.

Brooks moved home to Detroit in 1975 to take care of his ailing mother, and while his national profile took a hit, he continued to be a creative force on the local music scene. But by 1999, the time of the machete and whip incident and the year after he brandished an unloaded gun at another neighbor, Brooks’ mental health was in disarray. He was sent to prison for 32 months, and while he was able to stabilize there with medication, the experience aged his already ravaged body, and he passed away in 2005.

While Brooks recorded several albums as a band leader, all for small labels, a recently unearthed 51-year-old live recording will give more listeners a chance to hear Brooks as a leader at the height of his musical powers, pushing aside the salaciousness of his tragic personal life for an unadulterated view of his artistic prowess.

The music on Understanding, which was issued by the Reel to Real label as a special release for Record Store Day on July 17, comes from a Nov. 1, 1970, concert recorded at the Famous Ballroom in Baltimore and sponsored by the Left Bank Jazz Society. Many concerts promoted by this organization were recorded and have come out over the years, and Brooks’ album is another archival gem.

Brooks, then 32, led a band with pianist Harold Mabern, 34; trumpeter Woody Shaw, 25; tenor saxophonist Carlos Garnett, 31; and bassist Cecil McBee, 35, that sizzled through two hours of music covering just six songs: Miles Davis’ “The Theme” closes the concert at a concise four and a half minutes, but the other five tracks clock in at 20-plus minutes each, and Garnett’s “Taurus Woman” maxes out at nearly 33 minutes.

The recording is hot but not distorted, and it captures the band in tremendous form, playing off modal forms that swing hard but that touch on some of the fire and fury ignited by free jazz. Shaw, in particular, sounds like he’s wielding a flame thrower, and Brooks is always there to support the trumpeter’s excursions with an elastic push-and-pull that propels the music. Shaw throws down a nearly 11-minute solo on the opening track, “Prelude to Understanding,” and it’s likely that listeners — then and now — had to catch their collective breath even more than the trumpeter did.

Proceeds from Understanding benefit the Detroit Sound Conservancy, which works to conserve artifacts from the city’s musical past and educate the public about its history, and the whole reissue stresses Brooks’ connection to his birthplace and the jazz explosion that happened here in the 1950s. The drummer’s fellow Motor City musicians Louis Hayes, who preceded him in Silver’s band, and saxophonist Charles McPherson, Brooks’ Northwestern High School classmate, are interviewed; another classmate, journalist and educator Herb Boyd, contributes a short reminiscence of his friend, as does Detroit Sound Conservancy Executive Director Michelle Jahra McKinney, who’s an archivist at the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History; and former Detroit Free Press jazz and classical critic Mark Stryker, author of the book Jazz From Detroit, did the excellent liner notes, which really help listeners understand the mechanics of the music on Understanding. (McBee is also interviewed.)

Understanding is more potent than a machete, a bullwhip, an unloaded pistol. Those episodes were aberrations in a creative life; Understanding displays the bigger picture, the life for which Roy Brooks should be most remembered.Ěý

|

| Ěý |

|