Welcome to Tinderville,Ěýpopulation 60,000 — and growing by two or three every day.

Tinderville is the name a visitor gives to Dave Tinder’s ever-expanding collection of photographic postcards, a community of cardboard rectangles crowded into vintage oak cabinet drawers inside his suburban Detroit apartment.

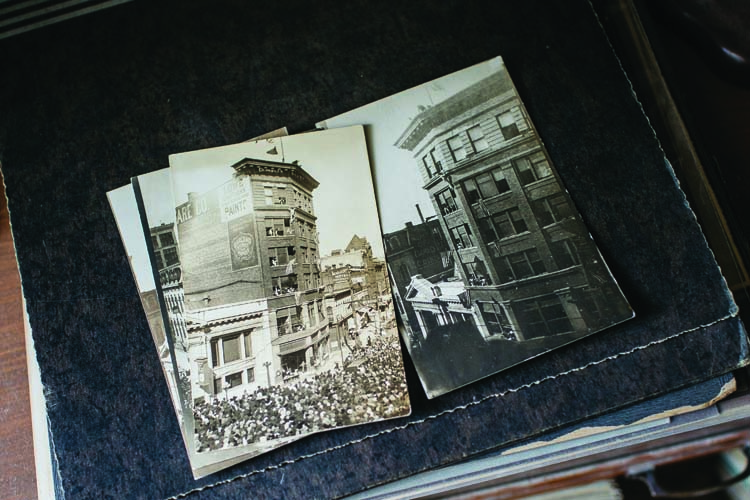

Most of the cards — commonly referred to as “real photo postcards,” or RPPCs — are a century or more old. The quaint images represent a cross-section of Americana in the early 1900s: barn raisings, airships, paper moons, locomotives, trolley cars, vaudevillians, blacksmiths, logging camps, Model T Fords, coal and ice delivery wagons, Main Street storefronts, and one-room schoolhouses.

The black-and-white or sepia-toned photographic postcards are distinguished from the glut of mass-produced color postcards by their singularity. Some were formal shots created by professional photographers, often inside studios or arcades. Others were made by ordinary folks using a simple, inexpensive Kodak camera that made postcard-size negatives.

They were processed by Kodak or local photographers. Each came back with a printed backing. All someone needed to do at that point was add an address, a penny stamp, and maybe a message.

Until the craze finally fizzled out around the time of World War I, untold millions of these one-of-a-kind images were mailed, with many more tucked inside letters, scrapbooks, or family albums.

An Impressive Assembly

On his way to becoming a noted authority on early Michigan photography and assembling his impressive collection on a limited income, the 88-year-old Tinder has had to make a few choices as to what’s essential in his life and what’s not. He doesn’t have a stove, preferring to zap Vienna sausages inside a small microwave. The last TV he owned was stolen in the ’70s. The battered orange futon dates back several presidential administrations.

Often the only light inside the cramped apartment is the glow from the computer screen as he waits to bid on another online auction.

“I’m a child of the Depression,” says Tinder, an Ohio native who moved to Flint as a youngster in the 1930s. The retired product development engineering manager collects strictly Michigan-related RPPCs. They are filed alphabetically by county and town, then arranged within each town in a series of subsets: bird’s-eye views, street views, industrial scenes, portraits, and so on.

Like most collectors, Tinder has his favorites, such as obscure railroad depots, mail carriers, and automobile-related cards.

So-called disaster cards — cyclones, train wrecks, fires — also are popular with collectors. Tinder appreciates calamity laced with irony. He pulls out a series of cards depicting an ice warehouse hit by a blaze. The walls are burned down, revealing huge blocks of ice left intact.

He rummages through another drawer and extracts a card showing “The Human Fly” scaling the side of the Hanselman building in Kalamazoo in 1916. Half the population of nearby Mendon turned out to watch, unaware of a greater spectacle taking place back home.

“While they were gone, a fire broke out and most of Mendon burned down,” says Tinder, producing several RPPCs of the town’s charred ruins. “There wasn’t anybody around to put out the flames.”

Triggering Passions andĚýa Business

Doug Aikenhead grew up on Detroit’s west side and earned an MFA in photography from Cranbrook. He became attracted to photo postcards after buying a handful at a garage sale in 1977.

“One was a downtown view of Calumet, Michigan, in winter,” he says inside his Ann Arbor home. “Three others showed a shipwreck in Keweenaw. That triggered something.”

Photo postcards allowed him to combine two passions: photography and history. His pastime became a business after he left academia two decades ago. The best cards, he says, are those that combine “an arresting picture and historical relevance.”

He’s particularly fond of photographer Louis Pesha, “one of the most prolific, most skilled postcard photographers of the period,” he says. “The back porch of his studio faced the St. Clair River. He did these wonderful postcards of freighters.”

Pesha died in a 1912 auto accident, leaving his wife to carry on the business. “She ran it for about 10 years,” Aikenhead says. “The story is … she dumped thousands of negatives into the Detroit River. They’ve never been found.”

A Price to Pay

Postcard shows, once supplemented by online auctions, are now being slowly supplanted by them, Aikenhead says. “The majority of them used to be sponsored by local postcard clubs, but those events are getting smaller and fewer.” Most successful shows are now professionally managed. Longtime shows in Kalamazoo and Lansing are still popular draws.

Tinder generally pays between $10 and $40 for a photo postcard, though if there’s something that’s especially appealing his wallet can open a bit wider.

Aikenhead gets an aching head thinking about the number of times he has shelled out $250 or $300 for a card. However, as with any collectible, the right kind of card can fetch much more.

A few months ago, a deep-pocketed collector outbid several others for a postcard featuring a constellation of head shots of the 1906 Detroit Tigers. Among those pictured on the card was a fresh-faced outfielder named Ty Cobb, who was then 19 years old and in his first full season. It was Cobb’s earliest known appearance on a baseball RPPC.

The card, which originally could be bought for a couple of cents at any downtown drugstore or tobacco shop, wound up selling for a rousing $2,121.

Slices of Life

Aside from its aesthetic qualities, a photo postcard can offer a one-of-a-kind slice of social history: a young man writing of life in a lumbering camp, for example, or a transplant to the city asking her farm family to make sure they take care of her pet duck.

One card from a private collection shows a young boy and his new dog, posed in front of their Detroit home one snowy day in the 1920s.

The dog apparently was a Christmas present. On the reverse is the inscription: “Scyba, Nine months, Scotch Setter. Run over at Lakewood Theater Lakewood & Jeff[erson] Detroit Mich. Feb. 25, 1923. Had him 2 mos.”

There is a growing acceptance of photographic postcards by academic institutions. Tinder’s cards are earmarked for the William L. Clements Library at the University of Michigan. They will be added to the collection of 19th-century cabinet photos, stereoviews, and cartes de visite he previously donated.

“Libraries and museums have a strong interest in photographic postcards, and they’re contending with private collectors,” Aikenhead says. “But while the pool of collectors grows, there’s a finite supply of cards. That can drive up prices.”

Unlike Aikenhead, who buys and sells cards at shows around the country, Tinder is strictly a buyer. On this day he taps a couple of keys and places a winning last-second bid on eBay.

This particular card is of a crowded car ferry dock at Mackinaw, circa 1920s. The $73.77 he bid is more than he wanted to pay, but it was too nice a card to pass up.

“Well,” the mayor of Tinderville says, “that’s one more for my collection.”

|

| Ěý |

|